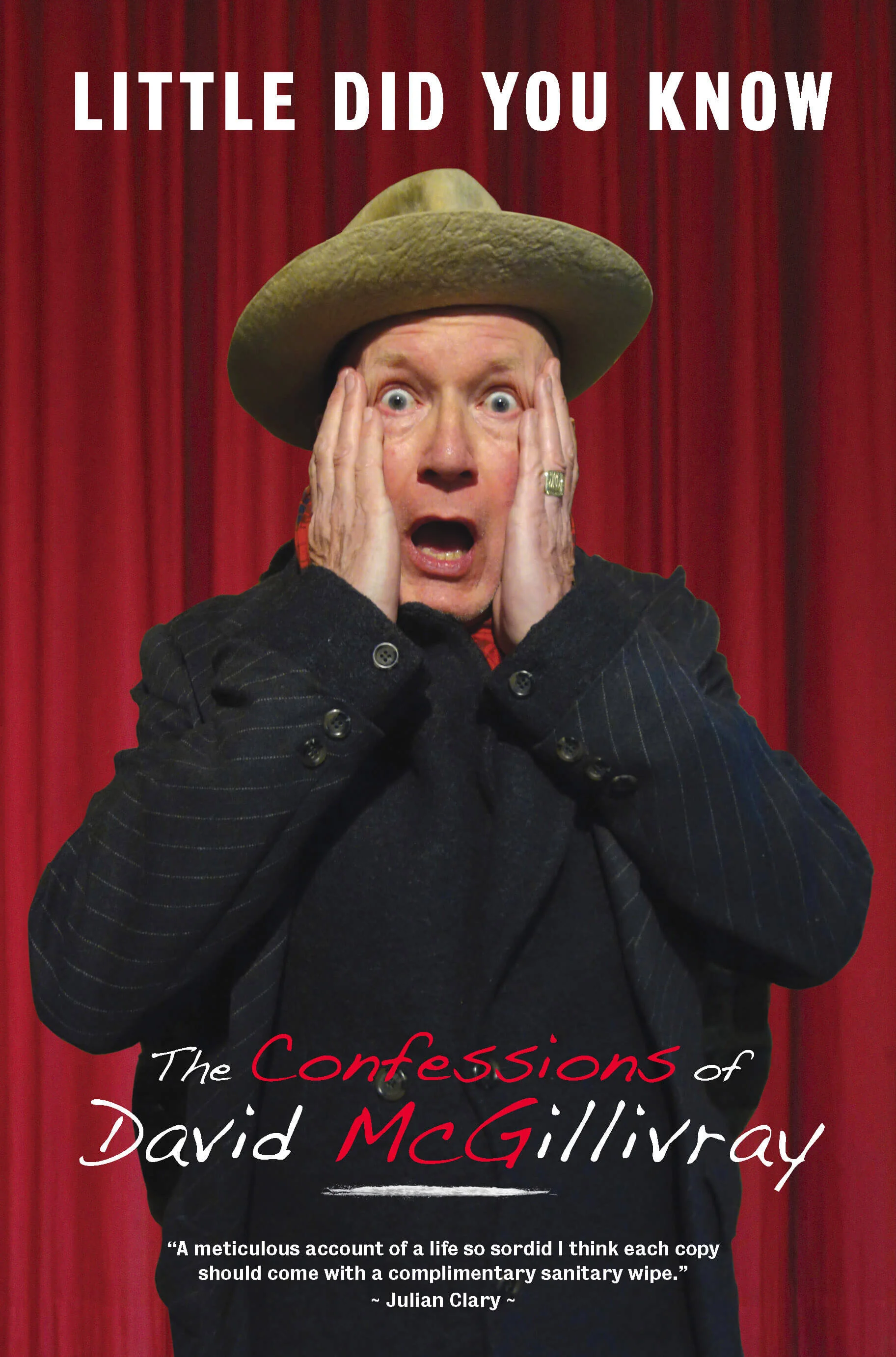

Little Did You Know: The Confessions of...David McGillivray

(Fab Press, £20)

Author, actor, radio and television writer-presenter, screenplay author, cinema and theatre director, comedy scriptwriter, magazine journalist, film extra, movie reviewer, sex historian... David McGillivray, or McG, as he is called by his friends (although he’s not the US producer-director, born Joseph McGinty Nichol, also known as McG) has had all of these jobs in his up-and-down career, a man with at least twelve lives and maybe more. His thirteenth life, his time as an uppers and downers drug dealer, was probably the most lucrative of all his day-to-day jobs and he doesn’t seem to mind owning up about this and most of the other questionable things he got up to during his seventy-something years.

At the launch of this volume of confessions he admitted for most of his life his main preoccupation has been with sex. Whether this led him to write the sexploitation screenplays he was commissioned to do is a moot point because for much of his soft porn days at the typewriter he wasn’t getting any sex. In fact there was more violence than sex in his screenplays, although the two often went together. McG’s first film as a writer was White Cargo (1973), David Jason’s second feature film after many years of television appearances. The actor’s only other film had been Andrew Sinclair’s prestigious version of Under Milk Wood, with Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor among a star-laden cast (Peter O’Toole, Glynis Johns, Sian Phillips, Victor Spinetti, et al).

David Jason’s next film was Richard Lester’s Royal Flash with Malcolm McDowell, Alan Bates, Oliver Reed and Tom Bell, but in between he appeared in White Cargo (aka Albert’s Follies), playing an ordinary guy who, in Walter Mitty style, yearns to be a superhero. It was not the funniest comedy ever written, as McGillivray himself would admit. He was charged with rewriting director Ray Selfe’s original script which had been conceived with The Goodies in mind. McG rewrote it in three days but then Jason suggested changes and the distributor wanted nude sex scenes to be interpolated. The roles of two Special Branch officers played by Hugh Lloyd and Tim Barrett were first meant for Morecambe & Wise. McG wrote himself a (literally) walk-on part as a customer in a carpet shop. Say no more – McG’s talents as an actor had yet to be determined. The finished film, which was neither sexy nor funny, ran for just over an hour and was released as the bottom half of a double-bill with The Stewardesses, a 3-D sex comedy. However, McG had arrived as a screenwriter and even though David Jason wanted his name removed from the credits, White Cargo didn’t appear to have damaged Jason’s career either as he went on to bigger and better films, but mainly stage and television work including Only Fools and Horses.

The Hot Girls (1974) was a short, 40-minute sex film with what appears to be no redeeming features except for McG interviewing girls about their sex lives. I’m Not Feeling Myself Tonight (1976) was McG’s other ‘soft porn’ comedy, a screenplay about a sex research institute where a young scientist invents a sex ray that, under its spell, turns people on so that they immediately want to have it away. Perhaps it was meant as a satire on the British way of (sex) life in that it included an anti-sex campaigner in Mary Whitehouse mode called Mrs Watchtower. With not much real sex but lots of top-speed chasing around in Benny Hill fashion, the film nevertheless fielded such stalwarts of British cinema as James Booth, Graham Stark, Chic Murray, Brian Murphy, Rita Webb, Ben Aris and others who should probably have known better, and it included a role for McG himself, playing one of several party guests.

I’m Not Feeling Myself Tonight was McG’s fourth screenplay, but before that he had written two of the horror films he made with Pete Walker. While acting in White Cargo he wrote House of Whipcord to which director Walker had hoped to entice all sorts of famous actresses for the film, but his fantasy casting never worked on this film or any of his others. That said, however, Celia Imrie was happy to be in House of Whipcord, describing it as “my favourite film ever”. McG was sometimes pleased to make, Hitchcock-like, token appearances in his filmed scripts. In House of Whipcord he had a named but uncredited role, in Frightmare he was a doctor, in another horror film, Satan’s Slave, he was a priest, while Terror saw him as a TV reporter. However, in Schizo and House of Mortal Sin there were no guest spots for McG.

And that was that for McG’s sex 'n' horror feature career but his own company, Pathḗtique Films, produced a series of short films from 1980 including some horror shorts called Worst Fears. His first film as producer was The Errand, directed by Nigel Finch of the BBC’s Arena television arts programme, who McG knew through Look, Stop, Listen, the BBC Radio London daily arts slot that he was co-presenting. McG then went on to produce more shorts and documentaries, culminating in his documentary on the grandfather of gay porn films, Peter De Rome, who gave McG a script by a famous personage, Trouser Bar, in which he invited many of his colleagues (Julian Clary, Barry Cryer, Nigel Havers) and friends, including moi, to appear as bystanders. It did very well on the short film awards circuit and can be found on the DVD of Boys on Film, volume 15.

But there were other irons in the fire for McG including television documentaries for Man Alive and Arena among many others, often on sexual themes including a film of his own book Doing Rude Things, celebrating the British sex film industry from the 1950s to the 1980s. As well as being a film-maker McG had also been a reviewer for Time Out magazine and for a time was assistant editor of the British Film Institute’s Monthly Film Bulletin. His abiding interest in chocolate led to his writing a column on the subject while I was editor of What’s On In London magazine. It was a first and a last – no other publications have ever repeated the idea.

Other strings to the McGillivray bow include writing comedy scripts for Julian Clary’s stand-up routines and some of his pantomimes – “my jokes are the ones that don’t get laughs,” he claims. He has also written a BBC local radio show for La Voix, a female impersonator. Drag on radio? Well, it has been done before – just think Norman Evans, Old Mother Riley, Hinge & Bracket and Dame Edna Everage. He once sent a one-off joke to the BBC for The Dave Allen Show and it has earned him a modest living ever since. And for many years he has been and still is a radio programme previewer on Radio Times magazine.

McG wrote his first play at the age of nine. Decades later he created a theatre company, Entertainment Machine, a touring theatre group for The Farndale Avenue Housing Estate Townswomen’s Guild Dramatic Society, a professional group that pretended to be amateurs. He co-wrote several plays for them (which always go wrong) with the late Walter Zerlin Jr. They were very successful for a time until touring eventually became unprofitable. However, he has always managed to reinvent himself, but how did McG get here from there?

‘There’ would be Palmers Green, the north London suburb, a quiet spot known only for its theatre, the Intimate, marking the beginning of McG’s road to success... Although born in West Norwood in south London, McG was brought up in Palmers Green from the age of six. His parents, who had met on war service in Egypt, had an odd marriage with lots of rows while McG’s father was both verbally and physically abusive. They had another, younger son, Paul, whom McG resented immensely. David attended Hazelwood Primary School and then went on to Winchmore Secondary Modern... and that is “where the story really starts,” as McG is wont to say in his memoirs, thus channelling his love of The Goon Show and in particular quoting his idol Spike Milligan, whom McG thought was a genius and perhaps an influence on his subsequent comedy writing career.

McG says he was a writer first, always was and still is to this day. He has kept a diary since he was twelve years old, so for him composition at school was no punishment at all. He regrets, perhaps for the book under review here, that he doesn’t have years one to eleven to draw on. At school he rarely got on with his teachers. One master, Mr Phillips at Winchmore found him to be “completely individualistic... and reluctant to conform”, as if that were a bad thing. In fact, the boy wanted to conform even though he was a born rebel. His aim was to be a movie star because he had seen the film Singin’ in the Rain in 1952 and wanted to be part of that way of life – he was just four and a half years old, but wrote letters to the likes of Rosemary Clooney and Doris Day. At school he felt he didn’t need an education to be a film star and he left with just four ‘O’ levels.

Probably through sheer boredom at Winchmore he invented his own school magazine called, naturally enough, Dave. It mostly comprised send-ups of the teaching staff which inevitably got him into trouble and ultimately got him expelled. He left school without a job and, although he didn’t become a film star, he did turn to acting at his local amateur theatre, the Intimate at Palmers Green, which at the time of writing is still extant, although its future, if it has one, is shrouded in doubt. He lied about his educational achievements (little) and his theatrical experience (virtually non-existent) on the strength of when in doubt – bluff. He worked backstage at the Intimate with occasional walk-on parts and developed an ambition to be a bit player in films, just like Marianne Stone or Michael Ward who became firm friends later on.

Thinking it might be easier to get a job in radio rather than films, in 1964 McG tried to be a DJ for the new pirate station Radio Caroline, but it came to nought. However, what he did find was an advertisement for a job at Gateway Films, a local firm specialising in educational and training films, which McG saw at last as his entry into the British film industry. It was, however, only a packing job in the dispatch department and he got sacked through sheer boredom. Then he worked at Contemporary Films in Soho, the heart of the film industry, doing repairs to films as they were returned to the company following cinema screenings. He was sacked again as he was too from Data Film Distributors, whose main work involved sending out the National Coal Board’s Mining Review newsreels to cinemas. There he met John Lawence, the man who was to guide him unwittingly to the house McG later bought in King’s Cross, scene of his future drugs raves. After that he applied to RADA but thought better of it, and drifted around town cleaning flats for other people and getting occasional crowd work in films such as Ken Hughes’ Cromwell and the odd Carry On film.

In 1968 by chance he happened upon a stall-holder in Camden Passage who asked McG to help him open and run a shop further down the market. After two years the shop went bankrupt. Back to acting he joined the Cameo Players, a Jewish company, where he met Walter Zerlin Jr, later to be his writing partner for Entertainment Machine’s ten ‘Farndale Avenue’ farces. By 1971 McG had moved to Kilburn and was reviewing sex films for the Monthly Film Bulletin but, because he wrote a piece on pornography for another magazine, he was subsequently sacked from the BFI, his last ever nine-to-five job.

But the story doesn’t end there. McG may not have had another nine-to-five job but he continued as a presenter on the BBC Radio London arts programme, Look, Stop, Listen, was still touring shows with Entertainment Machine and writing for Julian Clary. He became a director and presenter on the Premiere Movie Club, part of the Daily Mirror’s short-lived Premiere cable TV channel, where he was extremely well paid while it lasted. Little in McG’s life has lasted for ever, but he always somehow seems to reinvent himself in one way or another.

One major development was his becoming a drug dealer, a pastime he pursued very successfully for many years. At times sex went hand in hand with the drugs and he often managed to get off with people he had fancied from afar. Having taken many years of identity crisis trying to decide what he really was, sexually speaking, he went through stages of total virginity, then wanting to be straight, then bisexuality and finally coming out on the other side as solely gay, although through the changing years he has rarely had a long-term relationship.

As for his drug habits, he had experimented with happy pills such as purple hearts when he was a teenager because he loved the excitement of doing something illicit that gave his boring life a buzz. More recently in his ever rebellious career he was popular as a dealer in both low and high places, which was something of a surprise even to him, as he says in the book: “Today I have the social diary an ‘It’ girl would envy.” His King’s Cross parties were notorious and, far from regretting his new lifestyle, McG openly relished it, perhaps because it was really successful and that as well as the drugs gave him the buzz.

He had been sex mad at school from the age of fourteen, although little had happened to him then in that department. But he had sex on the brain and the passions of a lifetime coloured his outlook which became the driving force through everything he did in life. Could anyone, including himself, have predicted that, as he says, “I would end up as a bossy, anally retentive, gay drug dealer with a penchant for pornography?”

David McGillivray hides very little in these totally honest memoirs and is quite happy to paint himself in a bad light. The book is engagingly titled Little Did You Know and I, as a friend of nigh on fifty years, must admit I am surprised at how little I did know about McG as revealed in his confessions. He believes that “my diary is the only proof that David McGillivray has existed in different forms from the hack who is writing this today.” He obviously has no qualms about his life and he is never less than very busy, having done more than most in his long freelance career. Never ever the perfect student, he claims that the only thing of value he gained from school was how to touch-type, something useful for a born writer.

David’s philosophy is “never turn down an invitation or a freebie", presumably because you may meet someone who might just change your life. His confessions are truly personal, revealing but also very funny. I cannot recommend this book highly enough if you are looking for an insight into the human condition, warts and all, because Little Did You Know is a right old rib-tickling, bonk-busting, bodice-ripping, coke-fuelled, rip-roaring, unputdownable page-turner.

MICHAEL DARVELL