Making Monsters: Authors Howard Berger and Marshall Julius

by CHAD KENNERK

Growing up, what were the movie monsters that scared you? What did you imagine was lurking beneath the bed and looming behind the closet door? Frightening and thrilling images encountered in childhood have fuelled the imaginations of filmmakers to conjure new nightmares for the next generation.

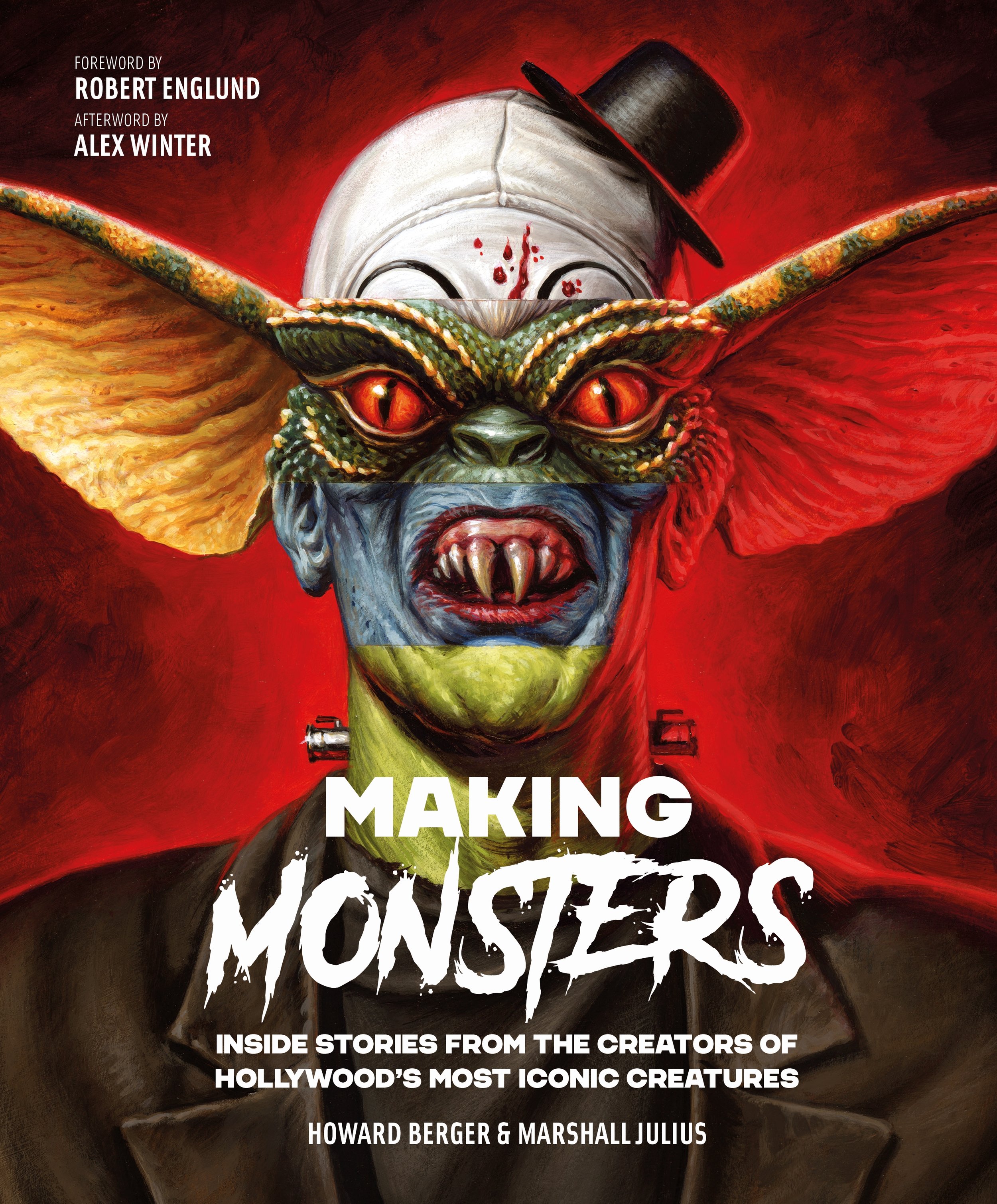

Following their hugely successful Masters of Make-Up Effects, Oscar-winning make-up effects artist Howard Berger and veteran film journalist Marshall Julius emerge from the shadows to continue their Hollywood Monsters odyssey with their next book, Making Monsters, an oral history of the monsters who made us and the magicians who made them.

In a spellbinding, devilishly detailed compendium of never-before-seen photographs and candid recollections from more than 80 film and television visionaries, Making Monsters pries open the crypt to expose the twisted geniuses that dreamed the nightmares, the hands that stitched the beasts, and the blood-bound Monster Kid community determined to keep the flame alive. With a welcome from dream demon Robert Englund and a final word from Lost Boys Alex Winter, along with wicked original art by Jason Edmiston, Graham Humphreys, Mark Tavares and Terry Wolfinger, Hollywood’s most iconic creatures come to life as Berger and Julius forge craft with camaraderie, inviting readers onto the set and behind the scenes.

In conversation with authors Howard Berger and Marshall Julius.

Film Review (FR): Your books are chock full of stories that make them instantly re-readable.

Howard Berger (HB): Yeah, and it's not a linear story. Same with Masters of Make-Up Effects. It is an oral history of film and the focus of what we like to do. A lot of film historians that have read the book contacted us and said, “This is a great history of what you guys do. There's no other one like it.” There are books about individuals — Mike Westmore wrote a book, and Rick Baker wrote a book. It's about connecting with our friends and people that are our heroes, that we admire, and getting to spend two hours with them, asking them questions and just having a casual conversation, which is really fun. That's how it all came about.

(FR): How did you arrive at the format of spreading interviews across the book?

(HB): It’s a very similar format to Masters of Make-Up Effects. Marshall and I knew we wanted something that reminded us of our childhood, when we had our monster books — that we still have. It’s about photos, and yes, there's text, but it's about the photos. It's also set up for people that have reading and learning disabilities, because I have severe dyslexia, and I always found it difficult to read.

Marshall and I came up with a font and a layout that we really like. It's really hit a nerve with people, because I think everybody that's creative has some sort of learning or reading disability, it seems. Everybody in my industry does, absolutely, and it was important for us to have a really interesting and engaging format. Marshall and I would hop on FaceTime almost every morning at three or four in the morning my time — of course, Marshall's in the UK, so it's eight hours ahead.

Marshall Julius (MJ): It was still early enough for me.

(HB): Yeah, it was still early for him and very early for me. We would go through the pages that the publisher and editor sent us and rework it all. We'd cut and paste and move it all over the place, because we understood what photos go with what text and where the text has to lie. We knew how we wanted this book to come together. Our fingers are super deep into every single page on both [books], but this one especially, because they gave us design credit, which is nice, because Marshall and I were virtually designing every single page ourselves.

(MJ): We did that with the first one, but with the second one, it was like, ‘It's not like it comes with any extra pay cheque, but it would be nice if at least we also got Designed By credit.’ Because there are whole pages and spreads in there that we did. Our photography is in there, and our stories. It's really very personal, and it's really personal for all the people that we interviewed as well. It feels like a family album, which is why, when we do the signings, it feels sort of like a class reunion. Everybody's a fan of everybody else. It's very inclusive.

(HB): Absolutely, Marshall. We made sure every contributor got a free book.

(MJ): I think for a lot of the people involved, it's a legacy thing. People wanted to be a part of it and to be included. They've got great stories. Howard always says that one of his favourite things about going to set is hanging out with his friends and sharing stories. That's what we wanted to capture in the books. It was really important that we cut out all the dry stuff, all the stuff that you know you're going to read and forget. We only wanted to include the best stuff that you would remember. Like if you went for a dinner party with these people. The next day you're not going to remember all the small talk necessarily, but you're going to remember those three or four blockbuster stories that they tell that you can then try out yourself.

That should be what the book is, because we interviewed 80 people, and we spoke to everybody for about two hours. That's 160 hours of transcription. That's enough for 10 books. So we could afford to be really selective, really harsh. If something didn't cut the mustard, it's like, ‘Sorry, that's not going in.’ Plus, a lot of people like the same films, so it's like, ‘Okay, so what is your favourite monster movie that isn't The Thing or American Werewolf in London?’ or ‘What's your favourite make-up that isn't Frankenstein's monster?’ You can't all say the same thing; otherwise, it's literally going to be a book about four films.

We got there, and we got some fantastic stories. The things that people attach themselves to as kids, the things that scare them or they get obsessed with — when you go back far enough, then you get real variety. The variety of stories is just amazing.

(FR): Looking back after volume two, what have been some of the most rewarding or inspiring moments for each of you?

(HB): For the first book, Masters of Make-Up Effects, Marshall had been chasing me for almost 20 years to write a book together, and when the pandemic hit, he said, “You have no excuses, because you're sitting at home.” And I went, “You're right.” We brainstormed, formulated and then started writing. It was a great opportunity for everyone. We had 67 people that participated in Masters. Everybody was stuck at home. Nobody was going out. So it was perfect.

(MJ): It was relatively easy to do the first one, because people weren't only free, they were bored out of their minds and desperate. We almost couldn't do it fast enough, really.

(HB): Then for this book, similarly, the actor’s strike happened. My show got shut down, and we said, “Well, let's do this. This will be cool.” It was nice, because Welbeck, who published the first book, reached out to us and said, “Masters was so successful that we want you guys to do another book, but we don't want a second Masters of Make-Up Effects.” They wanted something different, so Marshall and I pitched them another idea, and they really liked it. We got 80 participants. The first book is really about make-up effects, and this one is just about movies and monsters: how they affected us as kids and how they inspire us today.

We were able to really throw a very broad net in terms of having actors, composers, directors, and VFX people. It was really an incredible experience. For Marshall and I, who are complete, total cinephiles and fans of everything cinema, it was thrilling for us because we got to hear from the horse's mouth. We were talking to Charles Bernstein, who composed the music for A Nightmare on Elm Street and other movies, and he's saying, “Oh, I'll share with you the original handwritten sheet music, and you can put that into the book.” We were just really fortunate.

I'm lucky; I have a lot of friends in the industry, and I now owe them big time, because I've asked them numerous times to do so many things, which they're very, very generous about. It's been so rewarding. It was just fun to talk. Like Marshall said, as we have these book signings, that's a great opportunity, because so many times we're all on the road; this is a great opportunity for all of us to be in one room and be together, and it's so much fun.

(MJ): As a writer, I'm sort of mostly at home sitting in my pyjamas in front of my computer writing. It's pretty solitary, and I'm not a solitary person. After we did the first one, when we had a chance to come and do the signings, that was just the best time ever. I had so much fun being around everybody and actually getting to hang out with them in person, instead of over Zoom. To be sitting in on these signings with all these incredible legends, I'm not outside with my nose pressed up against the glass looking at how great that looks inside. I'm sitting at the table with them.

Obviously, Howard and I were both huge fans of all this stuff, but we come from different sides of it. Howard is a filmmaker and a creator, and I'm a fan and a journalist, so we have slightly different perspectives — an insider and an outsider perspective — but we both love the same things, and I think between us, we got a good round picture of everything, and we were able to fill in the blanks for each other.

(FR): All of the personal photos of future professionals playing dress-up and making monsters really helps draw parallels to the imagination and creativity that's so essential to these roles.

(MJ): We wanted people to read the books and to be inspired. The world is smaller now. Now you can connect with like-minded people more easily because of the internet and all. When Howard was growing up, all the other Monster Kids were generally spread out all over the world. They were usually the weirdest kids in their neighbourhood. They spent most of their time in their bedroom making masks and doing all of that. It was sort of solitary until they expanded their worlds. They went to LA, they got into films, and they created this huge community of these Monster Kids. That's why I think they're so tight, because they grew up without each other and they kind of found each other. It's really nice to see people finding their people, that tribe.

(HB): I kind of liken it to Close Encounters, where they have to go to Devils Tower, Wyoming. It's the exact same thing with people from all over the world. The first time I met Richard Taylor, who owns WETA and did The Lord of the Rings films, I was the very first make-up artist doing effects that Richard had ever met. We worked on Xena and Hercules in New Zealand together. He would do a block, and then I would do a block, and he had no contact with anybody else, just because it was New Zealand. That spawned this great relationship that I've had with Richard for 25 years, and it starts to build a community.

Peter Jackson was a guy who had just made Heavenly Creatures. [I remember] going to his house and looking at all his toys, and what a fan he was, but he wasn't the Peter Jackson yet. Everybody in the United States in the 80s kind of gravitated to Los Angeles because that's where it was. That's where the make-up effect shops were. Stan Winston, Rick Baker, and Greg Cannom – that's where you went. And you just stay friends with these people. With these books, it's maintaining my relationships with everyone that I've had for almost 40 years – so many people I've known forever. We all started out as kids when we were 17 and 18 years old, working for Stan Winston or Rick Baker.

Here we are in our 60s, and we're still doing it, which is incredible. We're still all great friends, and I think that's part of the fun of it all. I had a great time interviewing people. There were people I was nervous about [interviewing] because I'm still such a fan. I'm always nervous about Rick Baker, and I've known Rick since I was 12 years old. I break out in a little bit of a sweat because I'm just in such awe.

(MJ): Howard is different when we interview Rick Baker than he is with anybody else. There's just something about Rick. It's sort of like meeting Oz.

(HB): It's a religious experience for me. If I even meet up with Rick for lunch, I'm so nervous. I don't want to look like an idiot. I mean, he's such a great guy. I'm just so in awe of Rick Baker. I think that's good. I think that's what drives the fandom.

After we finished writing, everybody started sending their photos in for the book. Marshall and I were ping-ponging back and forth like, 'Look at this photo. Look at that photo. I've never seen this.’ Joe Dante sends us a bunch of stuff from the set of The Howling. Jason Reitman gives us photos of him and his dad, Ivan Reitman, on the set of Ghostbusters. Phil Tippett with Ray Harryhausen when he was 17 years old. It was so incredible.

Everyone was so generous and so kind and really on board. There wasn't anybody who said, 'No.' I reached out to John Carpenter’s wife, Sandy King Carpenter, and she said, "When I got the email request, I just looked at John and said, 'Hey, Howard Berger wants an interview.' And he said, ‘A hundred percent, yes.'” John doesn't do that. He was so on board, and he gave such a great interview. So much so that, Marshall, what's your phone ringtone now?

(MJ): Well, because this new book is not just about make-up effects, we were able to just go much deeper into monster movies. Whereas the first one was very much from the experience of putting on make-up or having make-up put on you, with the new one, it's all about making monster movies and making monsters. How do you write a good score for a monster movie? How do you direct a monster movie? Write a monster movie? How do you play a monster? We tried to look at all the different disciplines. There was so much more to talk about. That was what particularly interested us.

When we were talking to John Carpenter, what I really wanted to talk to him about was the writing of the Halloween theme; it's so iconic. It's like Close Encounters, those few bars, or the Jaws theme. It's one of those things that just immediately puts you in [the movie.] We're talking to John about writing it, and he's like, 'Oh, it's easy; it's bars.' He's very self-deprecating, but it's John Carpenter, for God's sake. Maybe, from his point of view, it's not a big deal, but to those of us who grew up on it, it's sort of like a god-tier creation. He was talking about it, and then he just did a few bars. And it was like, 'I can't believe John Carpenter just hummed the theme of Halloween for us.' I figured out how to put it on my phone, and now it's my ringtone. Every time I get a message, it always makes my wife jump out of her seat. It's very loud as well, but it's like, how could I not do that? It’s like if I had John Williams going, da-dum, da-dum. Of course, I have to.

We really didn't interview John Carpenter for the first one because he calls it 'rubbery monster shit', the kind of make-up effects. He appreciates it. He knows it's a necessary thing, and he loves the guys who make it, but it's not his number one passion. He's more into Dean Cundey’s cinematography and how it all comes together. Interviewing him for this book, we could talk about all sorts of different things with him. He was just totally up for it. It's great that he got his star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. Why didn't he get it 30 years ago? What else did he have to prove?

The thing that I wanted to mention is that I think that Howard and I both really respond to enthusiasm, to people who are really passionate. Because when they're passionate, then they're just all in; it's like, ‘What can I do to make this happen?’ How do you express your love for something? How do you create something that people will love? I think it's all about enthusiasm. That's one of the main reasons why I think these books are so successful, because make-up artists and that kind of filmmaker, they don't ever grow up; they never lose their enthusiasm. They never lose their excitement. I talk to Howard about new movies and things we watch. We don't like everything, but we want to see it, and we're excited when we see something that we really like. That never goes away.

These guys started off as fans, and they never got to the point where they’ve poo-pooed fandom. They still get it. That's why I think that the horror fans and make-up effects fans really have a much closer relationship with the creators than perhaps some other disciplines in filmmaking, where perhaps some people have had to make a bit of distance from their fans because it's like they have such different experiences. Whether you're a fan or a filmmaker in the world of horror, you just dig it so much. You're just super into it. We got a lot of enthusiasm coming towards us for our book, for the people contributing to it. We're getting that same sort of vibe from the people who are now excited to buy it. Without enthusiasm, without passion, and without the love for these things, what's the point?

(FR): Major influences have trickled down and inspired multiple generations. You mentioned Harryhausen and Marshall; you had a first-hand encounter. Is there anything that you haven't shared about that initial meeting with Ray?

(MJ): We were very excited to be able to include Ray Harryhausen in the last book. We could mention him as a sort of source of inspiration for people, but we couldn't really get into it because stop-motion animation is hard to shoehorn into a book about make-up effects. But when it came to Making Monsters, we actually gave him his own chapter. Ray Harryhausen is the only person who gets his own chapter.

I had just turned 18 and started writing. A Forbidden Planet store was opening, and he was doing some marketing with them. I'm not sure if he had one of his fancy film scrapbooks out, or if they just slipped him a few 100 quid. I don't know what the circumstances were that he was involved in that, but the fact is, they said, 'Would you like to interview Ray Harryhausen?' I said, ‘Obviously, would it be a phone interview?’ They said, ‘Well, he actually lives in London.’ I would have spent the last 15 years stalking him if I knew that he was in this country.

Going to interview him just blew my mind. If I ever had any doubts, which I didn't, about what I wanted to do for a living, the afternoon I spent with him [dispelled them.] He was so generous with his time. I was so excited, and I think he liked meeting his fans. I think he found it kind of comforting because he could see that the world was moving on from stop motion, and maybe he thought that he would be a little footnote in film history. But every time he met his fans, they said, “These films were important to us then, and they will always be important. They will always mean something.”

The second time I interviewed him, I had just finished the interview, and he excused himself to go and do something, and I was standing in his living room, and there were two other journalists that had just arrived. I looked over, and there was Ray Harryhausen’s Oscar. It was just there on the mantelpiece. I looked at the door, I looked at the guys, I looked at the Oscar, and I thought it would be so naff if I said to Ray Harryhausen, “Can I hold your Oscar, please? I've never held an Oscar.” I admit, if you want to know something I've not told anyone before, I did pick up his Oscar. I gave a little acceptance speech for winning an Oscar to the other two journalists there, and they looked at me like I was so naughty; they just couldn't believe it. I got my t-shirt and sort of polished it and put it back. So that's pretty shocking, but I didn't damage it, and I didn't put it in my bag.

Honestly, there was so much stuff in his house. Every model that he'd made, he had storyboards, and he had scripts of everything. It was such an incredible wonderland. I still think about it. Once you do an interview like that, how could that possibly be beaten, except maybe interviewing Howard the first time we met, and he made me up like Mr. Tumnus. That was also pretty good. And I got to hold Howard's Oscar that day. Maybe it's meeting someone and manhandling their Oscar. That's it – a lifelong obsession, maybe.

(FR): Howard, you had some exceptional correspondence when you were young. What does Howard's Book of Knowledge contain?

(HB): I started writing to people early on. I was able to hunt down Rick Baker and Stan Winston, but I knew that Dick Smith lived in Larchmont, New York, so I started writing to him, and he would write back. I would ask questions, and he would send me formulas and notes, and I saved them all. I have a giant book, Howard's Book of Knowledge, and it's filled with notes and letters from Dick and other people too. There's some Chris Walas stuff from Gremlins and some Mike Westmore stuff, but the Dick Smith stuff is really important to me because I still use it. I still refer to those notes. The blood formula that Dick created in the 70s, I still use, and we use it in my studio at KNB EFX Group. It's the base of all the blood that we make, and it's the best blood.

I look at it all the time, and it brings me back to being a kid, and all the Dick Smith letters have his letterhead, 'Dick Smith Make-up Artist', and on the side is his home address. He was always open to talking. You just couldn't call him during dinner, and if you did, he'd get really pissed. There were real specific times. I never did that, but I have friends who got chewed out by Dick Smith because they called at the wrong time. Dick was the guy who you call, and he's like, “I'm very busy right now; I really can't talk.” And then four hours later, he's like, “I've got to go now.” So he enjoyed it, and it's kind of like what Marshall was saying about Ray Harryhausen; Ray saw the end of his career coming, and there were people like Phil Tippett that were advancing what he had planted. He planted the seed, which was a magnificent seed, and it grew into multiple trees. But then there were people like Phil, who then took it farther. Dick was that way too.

Dick would always say, “You know, all of you have surpassed me. You've all surpassed me.” We never believed that. We would always go, “That's not true, by any means.” But he's like, “"No, I look at what you guys are doing today,” because we were entering a whole new world of prosthetic work, using silicones and things that Dick never, ever used. He was so fascinated by technology and watching it grow. And really, it meant a lot to him. Towards the end of his life, I saw him six months before he passed away, and we went to lunch. And he got very emotional about it, because it was a table full of us that wanted to take him to lunch, and we did it often. And he just would say, “It's amazing; I look around and there are thousands.” I'm like, “There are hundreds of thousands of people that do this because of you.”

It’s really a matter of keeping Dick's knowledge alive, which is about sharing and education, which is super important, and keeping his memory alive, which I think we're doing a really good job at. The Academy Museum in Los Angeles has done a great job as well. They know how important Dick Smith was to the film industry, and it's really wonderful to see that continue. We need everybody to keep remembering. There's Dick Smith, and there's Ray Harryhausen, and there's Rick Baker, and all these amazing filmmakers. Everybody we spoke to all had the same greatest hits. They all love The Thing, and they all love An American Werewolf in London. They all love Dick Smith.

J.J. Abrams wanted to be a make-up effects guy, and Dick Smith had the Dick Smith Make-up Course. J.J. submitted for it when he was younger, and Dick didn't think he had it. He said, “You know what? You shouldn't do this, but you should be a filmmaker.” J.J. Abrams became a filmmaker and not a make-up effects guy. When we're talking about like-minded people, it's almost like Invasion of the Body Snatchers. You meet somebody, and they turn out to be a massive fanatic.

Like Marshall was talking about Ray Harryhausen’s Oscar. I was working with Tom Hanks, and I said, “Well, what's one of the greatest things that you ever did?” And he said, “I got to present Ray Harryhausen with his Honorary Academy Award. I'm a huge Jason and the Argonauts fan; I love Ray Harryhausen. My most thrilling moment was getting to meet Ray Harryhausen.” You wouldn't think that, but there are all these people in the industry that love monsters. They're obsessed.

We interviewed Simon Pegg, who is a huge monster and movie fanatic. He'll talk about anything, and he's such a fan as well. That’s what binds us. We're all professionals. You talk to Joe Dante; he's been at this since editing for Roger Corman in the late 60s and 70s. And the guy is still a massive fan; he loves movies. He goes and sees everything. He and John Landis are movie buddies, and they go to movie theatres and see stuff all the time. Aside from this being what we do for a living, in everyone's personal life, they are still crazy about film and about monsters. It's a fantastic community, all very kind and all very like-minded. That's what brought these books together, and that's what makes these books really fun and enjoyable, because we were able to get some great memories.

Marshall and I crafted all the questions, but we also tailored everything to individuals. When Jason Reitman got his book, he called me immediately and said, “That photo you put in of me and my dad really made me emotional; I really appreciate that. I love the fact that my father's in your book with me.” We've gotten a lot of response from people who really feel well represented, which was a big thing. Part of our process was, once we interviewed and Marshall wrote everything up, we sent the quotes to each person to make sure everything was good. Some people rewrote, like John Landis, and some people were like, 'It's good to go.' With Phil Tippett, Marshall and I were like, “I think he's going to cut all this stuff because it's a little inflammatory.” And then Phil's like, “Nope, I like it, print it all.”

(MJ): The best thing about interviewing, especially the older guys, is that they just don't give a shit. It's very positive, the book, but there are a few things that are the craziest stories that you're surprised that they told us. And they're the crazy one in it; it's their mad behaviour. Then we write it up and send it. Howard’s like, “What's the worst that can happen?” In terms of due diligence, if you send everybody their stuff, you give everybody the chance, then there's no, ‘Oh, I wish you hadn't said that.’ People felt free to talk to us because they knew that they'd have a chance to tinker with it afterwards.

(HB): Representation was really important. It's not a book about slagging somebody off or anything like that. That's not what our interest is at all.

(FR): What's a deep-cut monster movie that you'd recommend?

(HB): One of the first films that really inspired me as a little kid was The Thing with Two Heads with Rosey Grier. I just watched it again, and it's actually really good. I mean, it's cheesy 70s crap, but it's got a two-headed Rick Baker gorilla in it, played by Rick Baker. That really blew me away. I'd never seen a gorilla suit like that before. My dad had shown me the film, and I was like, 'Wow.' I was really, really young, and I think that film still works really well because it's about a lot of different things. It's a very racially charged movie. There's some cool make-up effects stuff. And you know how they got rain? I don't even know how they talked Ray Milland into perching himself behind Rosey Grier, who's a big, giant guy. It's just awesome. That's a pretty deep-cut monster movie, and it really sparked my interest in it. That's where I first heard about Rick Baker. I had read Famous Monsters of Filmland, which Forry Ackerman edited. I was like, 'Rick Baker, who's this Rick Baker guy? He's incredible.

(MJ): I would say, for me, it's all bug movies. There was this TV movie called Ants! [or It Happened at Lakewood Manor.] That was a crazy film. There are people just being rolled over with ants. I love spider movies, from Arachnophobia to Kingdom of the Spiders with William Shatner. What I like about those bug movies is that there were very few special effects involved. They just put tons of bugs all over the actors who wanted to be in a bug movie. This is what it means to be in a bug movie. In Arachnophobia, they were like competing to see who could do the most disgusting things. Some of the actors had spiders in their mouths, and there was no CG; there was just an actual live spider. I respect that. I love a good bug movie and Night of the Lepus.

(FR): If you could go back in time to see any production and witness a monster being made, what would it be?

(HB): For me, it would be going back in time to the set of Creature from the Black Lagoon. Being there and being able to go to Bud Westmore's shop at Universal Studios and see all those guys building that creature suit and really getting an idea of it. And meeting young Ricou Browning, because I got to meet Ricou when he was older.

(MJ): I think for me it would be the original King Kong. I just love that film. It's so full of mystery and adventure. I think it would be really fun to hang out on the set and to just see that come together and to learn from the man who inspired Ray Harryhausen. That would be pretty cool.

If I could go back in time but then come back, I would go to Star Wars and just fill my pockets with stuff. A lightsaber just went for almost 3 million quid. So I think I’d probably go there, and I would just say, “You're finished with this, George?”

(HB): “You don't want this lightsaber. It’s junk.”

(MJ): We now have stories about how they just threw a lot of that stuff out at the end of filmmaking, Christopher Tucker told us. Christopher passed away after the first book, but we included a story that we had spare for the new one, and he worked on the Cantina scene. And at the end of that, he just threw everything out in a skip outside. I still have nightmares about that. He said if they had any idea of the value, he would have obviously filled his car up with the stuff instead. But then he couldn't imagine that anyone outside of a mental asylum would actually give a shit. But that was just why Christopher was such an awesome guy, because he was so incredibly rude to everybody, but in the most thrilling, hilarious way. We were very, very fond of him. I mean, he's right; loving Star Wars is a sort of madness, but I'm fine with that. I don't want to be sane.

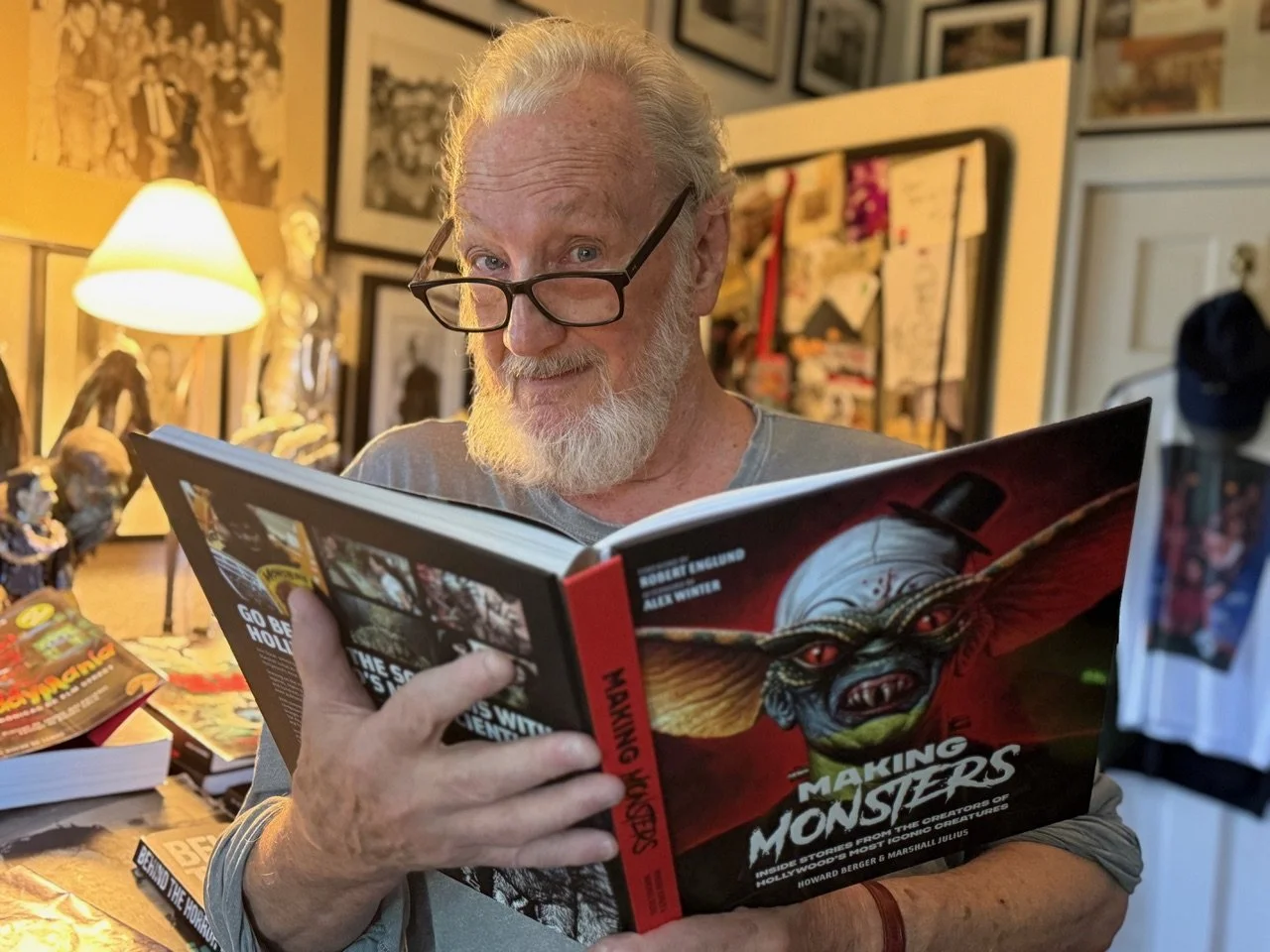

HOWARD BERGER is an Academy Award-winning special make-up effects artist with over 800 feature film credits spanning four decades. Over the course of Howard’s career, he has worked on such projects as Dances With Wolves (1990), Casino (1995), From Dusk Till Dawn (1996), The Green Mile (1999), Kill Bill 1 & 2 (2003), Oz the Great and Powerful (2012), Lone Survivor (2013), The Amazing Spider-Man 2 (2014), The Orville (2017-Present) and American Primeval (2025). In recognition for his work on The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe (2004) Howard won the Academy Award for Best Make-Up as well as a British Academy Award for Best Achievement in Make-up. In 2012 Howard was again nominated for an Academy Award for designing and creating Sir Anthony Hopkins' portrait make-up for the Fox Searchlight feature Hitchcock (2012). In 1988 Howard co-founded KNB EFX Group, Inc. For the past 37 years KNB has garnered its reputation as the most prolific Special Effects Make-up studio in Hollywood. He resides in Sherman Oaks, CA with his artist wife, Mirjam.

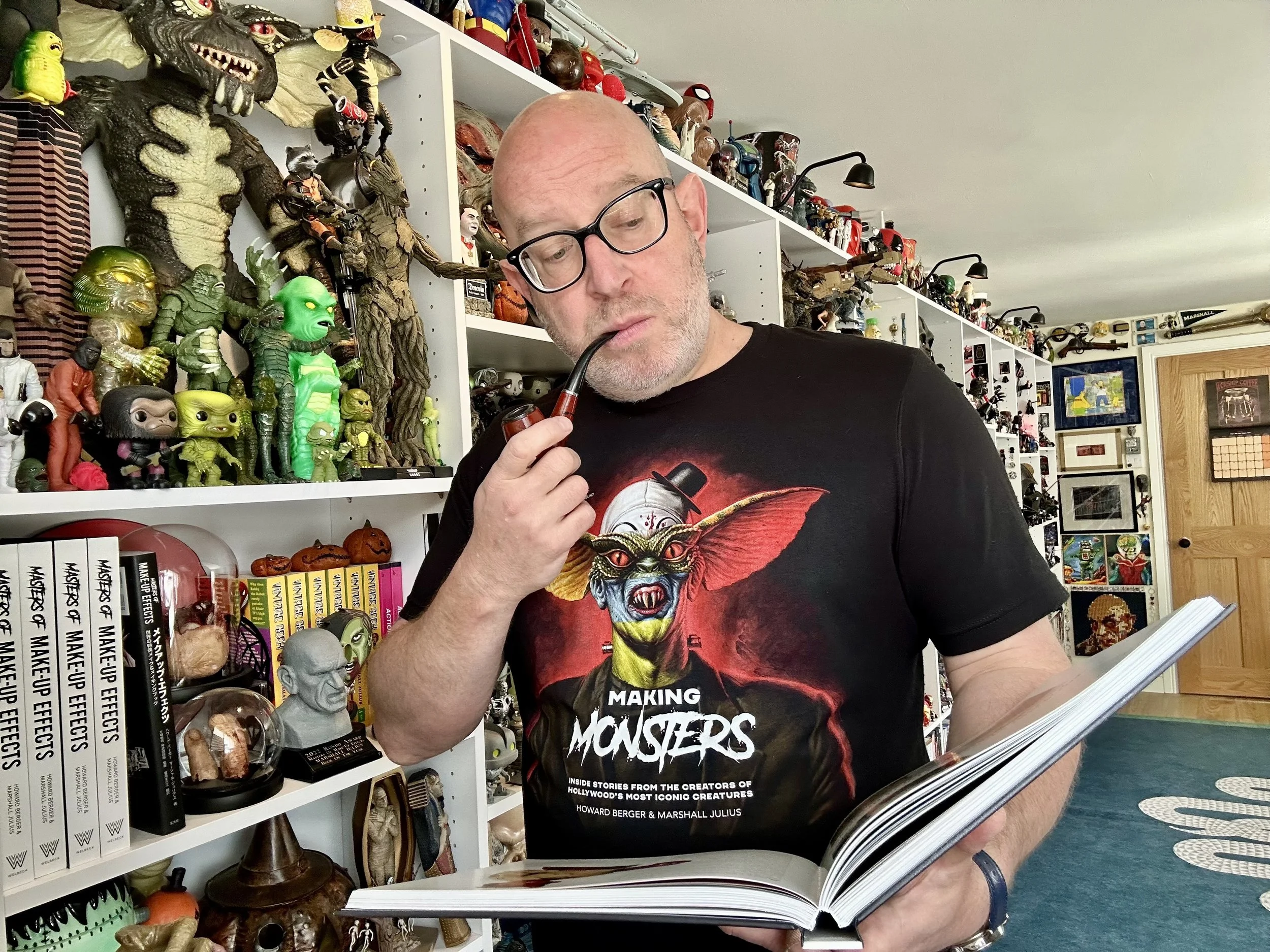

MARSHALL JULIUS, a veteran nerd with unbound enthusiasm for everything you love, is a film critic, blogger, broadcaster, quizmaster and collector of colourful plastic things. Also the author of Action! The Action Movie A-Z (Batsford Film Books, 1996), Vintage Geek (September Publishing, 2019) and, with Howard Berger, Masters of Make-Up Effects (Welbeck Publishing, 2022). Marshall lives in Norfolk, England with his wife Ruta and their hounds Merlin and Morgan.