The Small Back Room │ StudioCanal

by JAMES CAMERON-WILSON

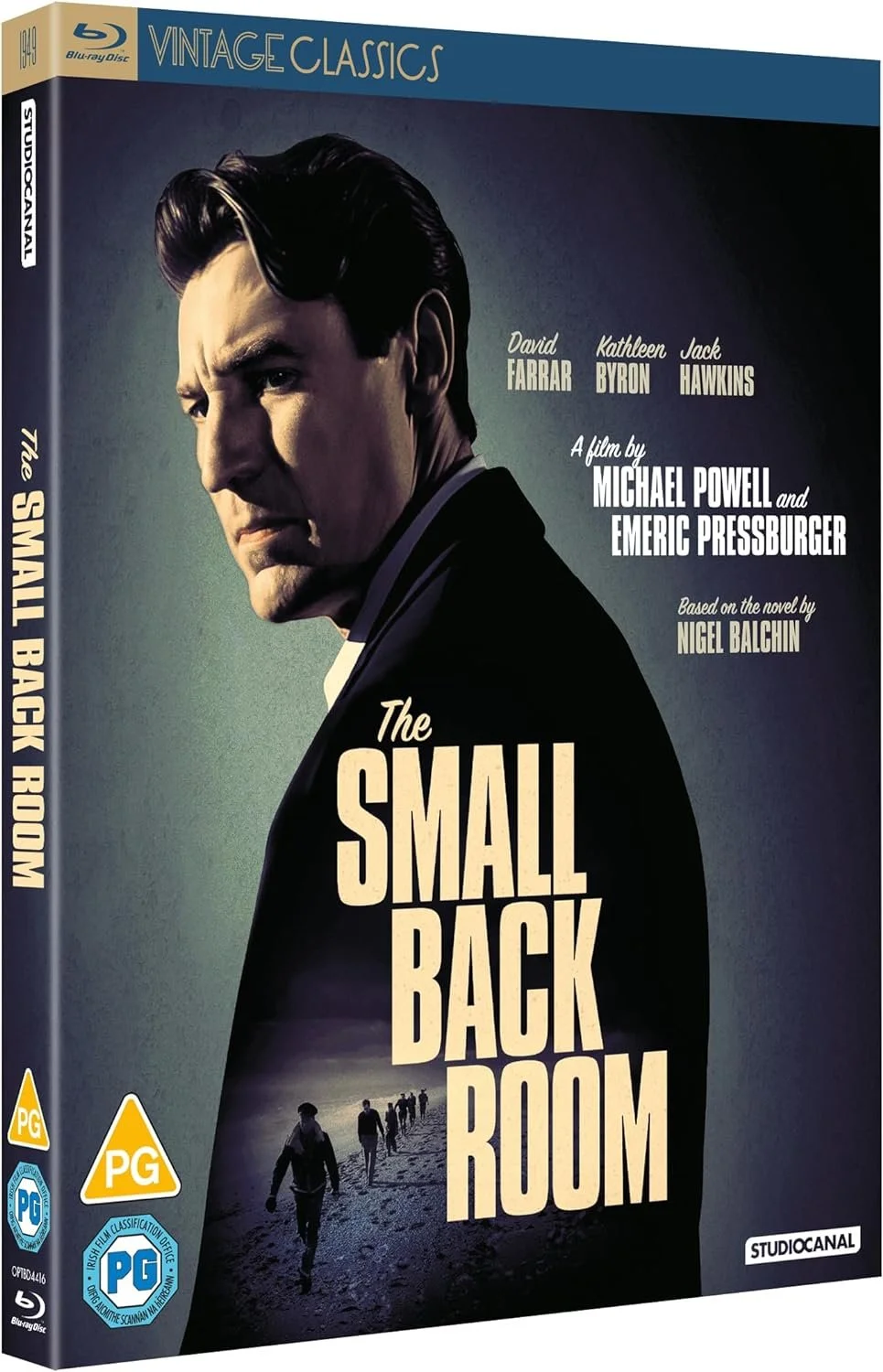

Hard to believe today, but Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s 1949 drama was a flop. A glum, perhaps cynical, claustrophobic piece of film noir shot in black-and-white, The Small Back Room was released just four years after the end of the Second World War – and it was not what postwar audiences wanted to see. Indeed, it is hardly one of the most celebrated titles in the Powell/Pressburger catalogue and I, for one, had never seen it before. Even so, having just watched this consummately photographed and magically restored work, I would say without hesitation it is one of my very favourite Powell and Pressburger films.

With the psychological complexity of a good play and replete with telling touches, it blends both the disciplines of Hollywood film noir with the Expressionism of the Weimar cinema of Germany, but with its own ineffable, stiff upper lip Englishness. This was more Michael Powell’s baby than his producing partner Emeric Pressburger’s, and so it has a more hard-edged carapace to it, with elements of Hitchcock and Billy Wilder’s The Long Weekend. Set in 1943, it concerns itself with the backroom boys of the war effort, great minds squirreled away in oppressive chambers, some beneath street level. And it is a very adult film, exploring the minutiae of human experience, being a story of love, war, alcoholism and a series of mysterious thermos-like objects that start appearing in the British countryside.

David Farrar stars as the urbane, charismatic yet troubled scientist Sammy Price, who struggles against the temptation of drink, even though it alleviates the pain of his damaged leg, a prosthetic limb made of tin. The ‘dope’, as he calls it, just doesn’t do the trick. Here is a world of largely grown-up men and women, attempting to do their best for their country, providing the film with a sophistication embalmed in a different vocabulary from our own, different manners even, so if somebody is described as “a bit queer,” they don’t mean he has homosexual tendencies. This is a world where there are sandbags everywhere and you can expect change from two and fourpence for a glass of Scotch. But besides the superlative script, the brilliant shadow play courtesy of DP Christopher Challis and the performances, there is no background music. The bombastic scores of Powell and Pressburger’s films have always proved problematic for me – the absence of which actually lends enormous tension to this film’s more suspenseful scenes of bomb disarmament.

And as so often with British films of this vintage and calibre, the many faces are instantly recognisable, with the cast including Kathleen Byron in the female lead (an intelligent performance), with support from Jack Hawkins, Geoffrey Keen, Sidney James, Bryan Forbes, Renée Asherson, Walter Fitzgerald, Leslie Banks, Sam Kyd, Michael Gough, Patrick Macnee, Cyril Cusack and an unbilled but instantly recognisable Robert Morley. The last-named stars in a wonderful scene in which he plays a minister who is introduced to the work of the backroom boys, including a magical, and I quote, “electric calculating machine – it does sums, sir.” At first the minister challenges the operator with a sum which he is able to answer off the cuff, so Robert Morley attempts a more difficult sum, the result of which seems so miraculous to him that he asks for the answer to be printed off for him. Then, with wonder in his eyes, he says, “I wish you could invent me something that could write speeches.” If he could see us now. Also out-of-time is the scene in which the army takes over Stonehenge to test out a new form of artillery. The dialogue, too, provides lines you wouldn’t hear in another movie, such as Jack Hawkins’ R.B. Waring despairing, “Oh, Lord, how sick I am of these people who know their jobs.”

And then of course there is the bonus material which, courtesy of StudioCanal Vintage Classics, are exemplary. There’s a brilliant, fascinating and informative video essay from Kevin Macdonald, who is not only the director of such films as the Oscar-winning One Day in September, and Touching the Void, The Last King of Scotland and The Mauritanian, but who happens to be the grandson of Emeric Pressburger. And there’s a documentary about the restoring of the film, explaining why they had to scan the original negative in London because of fears of what would happen to it being shipped on the “high seas” to America; there’s a piece on The Archers, the company set up by Powell and Pressburger – from veteran film critic Ian Christie; an interview with the cinematographer Christopher Challis; and some brilliant audio commentary from Charles Barr – not to mention Kevin Macdonald’s made-for-TV documentary The Making of an Englishman, tracing the life of his grandfather.

STUDIOCANAL’s release of The Small Back Room is now available on Blu-ray and in 4k

STUDIOCANAL is Europe’s leader in production, distribution and international sales of feature films and series, operating in all nine major European markets - France, United Kingdom, Germany, Poland, Spain, Denmark and Benelux - as well as in Australia and New Zealand. It owns the largest library in Europe and one of the most prestigious film libraries in the world, boasting more than 8,000 titles from 60 countries, which span 100 years of film history. 20 million euros has been invested into the restoration of 750 classic films over the past 5 years. Known for releasing a stunning roster of incomparable vintage classics titles, StudioCanal’s releases include outstanding thrillers, heart-rending masterworks, horror favourites, war dramas, Ealing comedies, and plenty of lesser-known gems. The collection boasts some of the greatest and beloved stars of British cinema.