70 Years of Film Review

James Cameron-Wilson's

Top Ten Films of the Last Seventy Years

It’s a Wonderful Life (1946; Frank Capra)

Singin’ in the Rain (1952; Gene Kelly and Stanley Donen)

My Fair Lady (1964; George Cukor)

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968; Stanley Kubrick)

Fanny and Alexander (1983; Ingmar Bergman)

Jean de Florette (1986; Claude Berri)

Raising Arizona (1987; Joel Coen)

Jurassic Park (1993; Steven Spielberg)

Borat (2006; Larry Charles)

WALL-E (2008; Andrew Stanton)

The idea of condensing seventy years of filmgoing (or, in my case, 43 years) is ludicrous. For starters, what we might have admired in the ignorance and excitement of our youth, might appear somewhat obvious and laboured to our older selves. Thus, the films I have picked for my ‘favourite’ top-ten – no Citizen Kane, for me – are titles that I have re-visited over the years and which have continued to yield fruits of immense satisfaction. Of course, it’s tempting to choose one film from each decade, but cinematic excellence doesn’t arrange itself so neatly. Having generally considered the 1970s to be the most creatively fertile, I surprised myself by not finding a film that I liked enough to include in my top ten. I’m in no hurry to see Taxi Driver yet again and while I admire and cherish The Godfather enormously, I wouldn’t exactly call it an all-time favourite. The same applies to The Godfather Part II, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and The Deer Hunter. Of all the films of the 1970s, the closest that comes to a ‘favourite’ is Annie Hall.

So, working chronologically from 1944, my first favourite is the bleedingly obvious It’s a Wonderful Life (1946). Few films have given as much joy to so many generations as Frank Capra’s immortal classic. Indeed, in America it has become as much a staple of Christmas day as turkey and Christmas stockings. Yet, unbelievably, it was a box-office disappointment on its release and secured not a single Oscar. It even attracted the censure of the Motion Picture Production Code for using words like “jerk,” “dang” and “lousy,” which were all cut from the final screenplay. Tut-tut. But what remains is a hymn to small-town America and the triumph of the human spirit. Sure, it’s sentimental, but its message that we all have an impact on the people around us is as pertinent today as it ever was. Meanwhile, the name George Bailey, the town of Bedford Falls and the guardian angel Clarence have become iconic markers in the history of cinema. And riding above it all is the effortlessly watchable and engaging James Stewart, whose comic timing is a joy to behold. Even after repeated viewings it retains the ability to move, to amuse and to charm, reminding us what a privilege it is to be alive.

James Stewart in Frank Capra's It's a Wonderful Life

Bypassing All About Eve, Sunset Boulevard and An American in Paris, I arrive at Singin’ In the Rain (1952). Gene Kelly and Stanley Donen’s co-directed film is simply a blast of joy. Cobbled together from a raft of previously used MGM numbers (‘Good Morning’ was hitherto sung by Mickey Rooney and Judy Garland in Babes in Arms), the 1952 musical is a love letter to the cinema, an exuberant parody of the transition from silent to talking pictures. Gene Kelly stars as the debonair silent movie star Don Lockwood, paired with the helium-voiced Lina Lamont, played by Jean Hagen. Pealing back the artifice of Hollywood with sardonic aplomb, the film is packed with eye-boggling dance routines, the effortless skill of Kelly and co-star Donald O‘Connor captured in radiant Technicolor by D.P. Harold Rosson. Even after all these years it is just as entertaining, funny, gleeful, inventive, charming and moving. And the stand-out title routine of Kelly, literally, singin’ and dancin’ in the rain, remains the most iconic dance sequence in cinema history.

Wet, wet, wet: Gene Kelly in Singin' In the Rain

Twelve years on, I alight on another musical, albeit one of a very different stripe. I might have opted for the superlative Psycho or the masterful Lawrence of Arabia, but for the pure, indiluted pleasure of repeated viewing, nothing does it like a musical. And, truth be told, my top ten favourite films could all star Audrey Hepburn. Having said that, the first half of My Fair Lady (1964), George Cukor’s peerless adaptation of Frederick Loewe and Alan Jay Lerner’s 1956 show, is not your typical Audrey fare. Much credit must go to the wonderful words culled from George Bernard Shaw’s original play Pygmalion, the sumptuous costumes and production design of Sir Cecil Beaton and the witty, tuneful songs (‘Why Can't the English?’, et al) – not to mention a perfect incarnation of the misogynistic Professor Henry Higgins by an utterly urbane Rex Harrison. Dramatically, Audrey may not have been up to the demands of playing the vocally-challenged flower girl Eliza Doolittle, but she certainly comes into her own as the lady of the title (from Mayfair, previously pronounced by her as “myfair”). Oh, and Marni Nixon dubs her singing sublimely.

Audrey Hepburn learns to speak proper from Rex Harrison's Professor Higgins in My Fair Lady

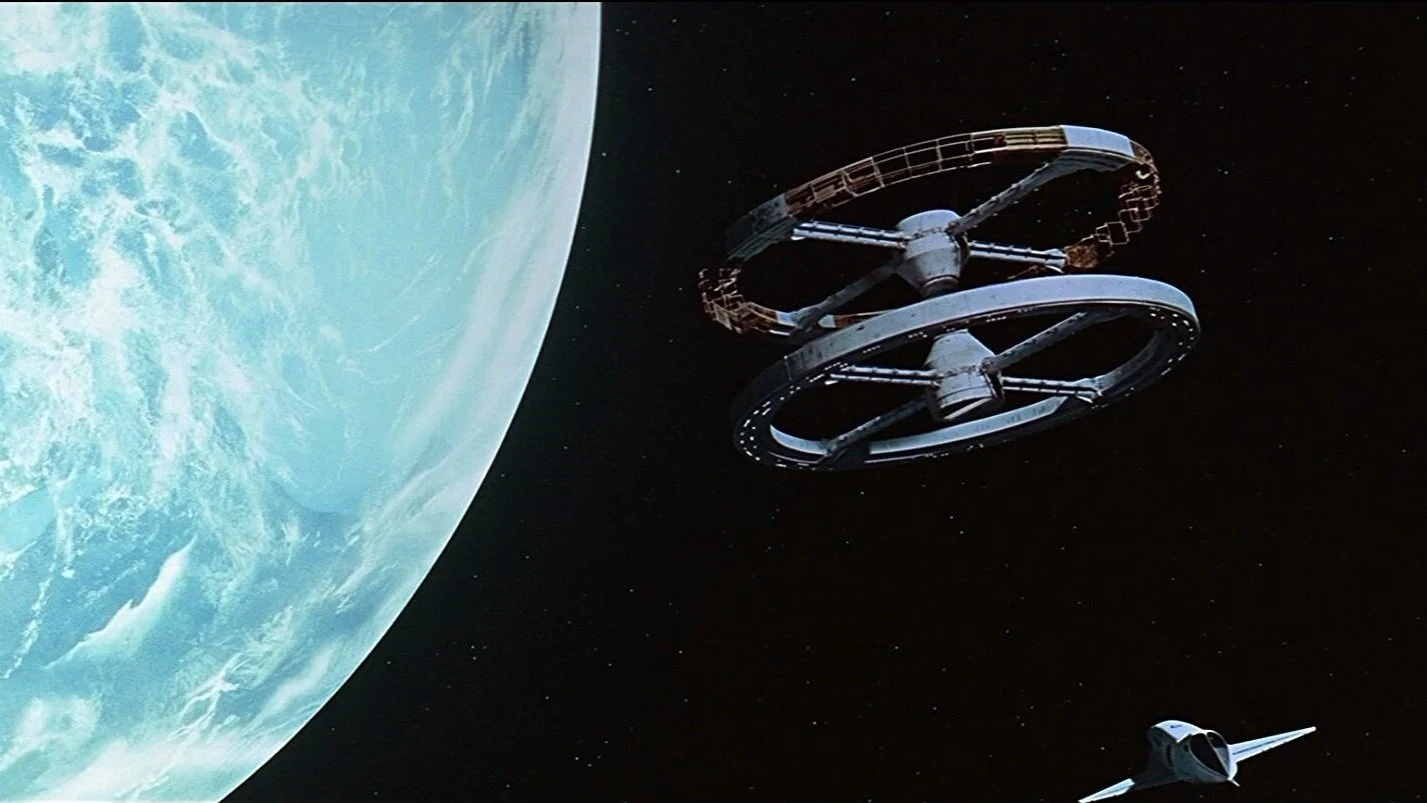

And then for something completely different. Indeed, after the release of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) science fiction was never the same again. While critics have praised the film for its technological feats and climactic ‘cosmic ride,’ 2001 is so much more than that. For instance, the use of sound has barely ever been surpassed – from the jubilant space waltzes set to the music of Strauss, to Gary Lockwood’s increasingly panicked breathing in his space suit, to the sudden eerie silences of the cosmos. Kubrick’s’ refusal to visualize the film’s alien presence is also a highly intelligent move – extraterrestrial existence is far more credible when we can’t even picture it. But it is HAL, the brutally expressionless super-computer, that is possibly the film’s ace card – a villain that establishes 2001 as the most disturbing film ever bestowed with a U certificate.

Spatial awareness: Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey

To many, Ingmar Bergman’s Fanny and Alexander (1983) came as something of a shock. Unlike the saturnine, deeply metaphysical films for which Bergman was known and deified, this sprawling family epic set in the spring of the twentieth century was a mosaic of fun, bonhomie, farce, tragedy and horror. While reflecting on a childhood similar to his own, Bergman’s film is not, in its director’s words, autobiographical. It is nonetheless a predictably visual banquet in which the production design jostles with the cast of sixty for breathing space as the strands of the narrative overlap in a labyrinthine cat’s cradle. Following the sumptuous and boisterous first act – chronicling the Christmas celebrations of the wealthy Ekdahl family – the film switches to drama with chilling effect, which, in turn, is superseded by the macabre and the surreal. Fanny and Alexander is an endlessly inventive and richly cinematic achievement, a smorgasbord of emotion, artistry and magic.

A typically lusty scene from Bergman's Fanny and Alexander

Claude Berri’s Jean de Florette (1986) is no less of an emotional rollercoaster ride and should, in fairness, be partnered with Berri’s Manon des Sources (1986). Both films – released four months apart – make up the two-part story of a slice of Provençal mountainside where neighbours jostle for the agricultural advantage of a natural spring (des sources). Based on Marcel Pagnol’s two-part 1963 novel L'eau des Collines – itself adapted from Pagnol’s screenplay for his 1952 film Manon des Sources – the film is an object lesson in storytelling. But even without the potent narrative throbbing at its heart, the film can be enjoyed on so many other levels: for Bruno Nuytten's rhapsodic cinematography, Eric Mauer's atmospheric sound editing, the glorious theme tune (borrowed from Verdi’s opera ‘La forza del destino’) and the uniformly superlative acting, from Yves Montand’s jovial and Machiavellian César Soubeyran to the wonderful character acting of the locals. Daniel Auteuil won a Bafta and a César for his part – as the scheming misfit Ugolin – but Gérard Depardieu is every bit as good as the hunchbacked Jean, whose infectious and misplaced optimism breaks one’s heart.

Gérard Depardieu and Elisabeth Depardieu in Jean de Florette

Also heart-breaking is Holly Hunter’s desire to have a baby. When Ed, the infertile cop she plays in Raising Arizona (1987), is handed a stolen baby by her criminal husband H.I. (Nicolas Cage), she erupts into tears, sobbing, “I – love – him – so- much!” It’s a masterclass in comic acting. But then everything in the Coen brothers’ unorthodox comic masterpiece is pitch-perfect: even the dissolves are witty. Mixing considerable style with an extraordinary energy, the film is blessed with reams of priceless dialogue (Ed, ever protective of her bebb-ee: “Mind his fontanelle!”), a lush visual palette (shot in Arizona’s Valley of the Sun) and a score – a symphony of banjo, whistling and yodelling – that is both exhilarating and piquant. And, seriously, the infant quintuplets that play Harry, Barry, Larry, Garry and Nathan act like they’re auditioning for RADA.

Randall 'Tex' Cobb in Raising Arizona

Steven Spielberg’s Jurassic Park (1993) on the other hand was not as funny. While there is plenty of humour in this classic monster movie, the film’s power lies in its ability to generate the awe factor in spades. A lot of ‘what ifs?’ are transformed into a rollercoaster ride of thrilling excitement as creatures from the past are resurrected to populate the ultimate theme park. As usual for Spielberg, he takes a tried-and-tested genre and reinvents its parameters. Perhaps his masterstroke – besides the ground-breaking special effects of the time – was to cast the genial, avuncular Richard Attenborough as the film’s villain. Attenborough’s John Hammond is, after all, just a megalomaniac who wants to create magic – not unlike Spielberg himself. He is a proud man, to be sure, but he is a puppeteer needing to please. But it’s the prehistoric giants that made Jurassic Park the success story of its time, creatures made flesh through the credible manipulation of genetic tampering. Spielberg made it all seem possible – and he was closer to scientific fact that he dared to believe.

Monsters, Incorporated: Richard Attenborough (left) shows Laura Dern and Sam Neill his dream, in Jurassic Park

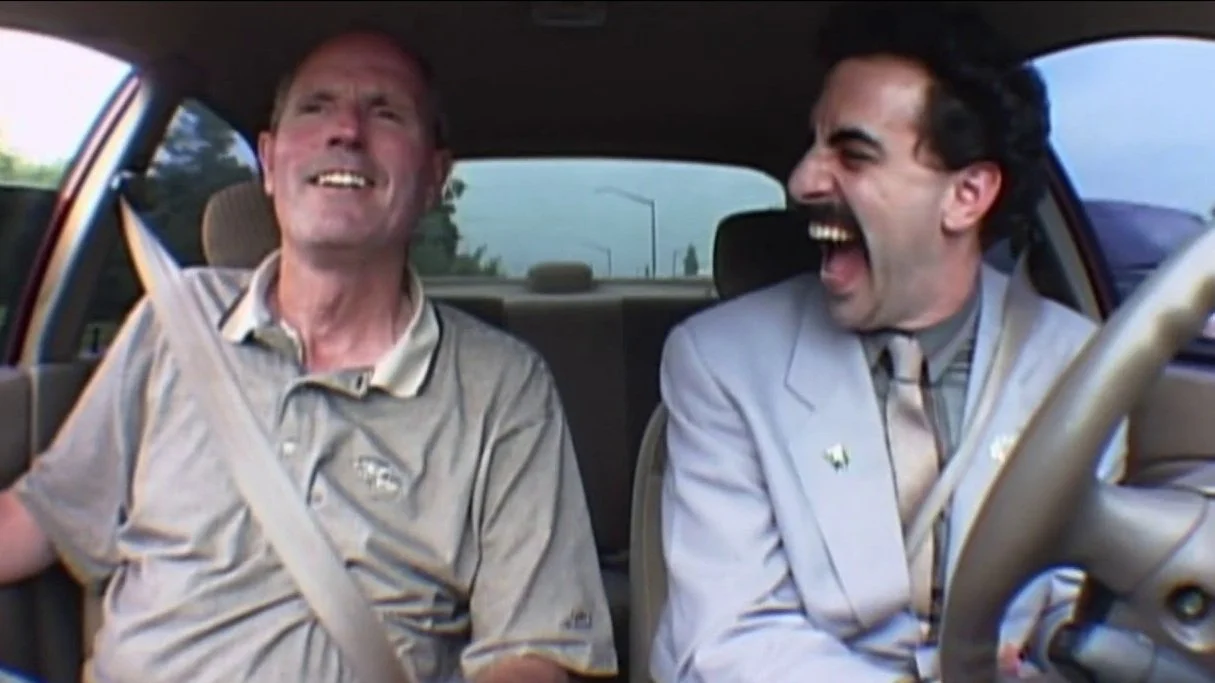

So, back to humour with Larry Charles’ Borat: Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan (2006), to give the film its full title. This was a new kind of comedy, a ‘documentary’ about America that exposed the smug entitlement of a nation accustomed to patronising Third World visitors. An equal opportunities offensive on everybody that the Kazakhstani TV reporter Borat Sagdiyev encountered, the film was a road trip designed to trip up the unsuspecting, be they Jewish, female, homosexual, bigot, snob, Christian fundamentalist or even the “chocolate-faced” Republican activist Alan Keyes. Of course, Borat, as embodied by the English comedian Sacha Baron Cohen, was not Kazakhstani at all, but a satirist prepared to risk life and limb in the name of his art. The joke was that the genuine interviewees thought that Borat was for real while, we, the audience, knew otherwise – and marvelled and guffawed at the interaction between real life and fabrication. This may be guilt-edged comedy, but one can’t help but laugh at the gullibility of Borat’s victims.

Victim of comedy: Sacha Baron Cohen takes Michael Psenicska for a ride in Borat

And so to my sole cartoon. One might have been tempted to choose the prelapsarian innocence of Disney’s earlier cartoons, or the sophisticated, knowing brilliance of The Lion King, Shrek or Toy Story, but I’ve opted for something that really struck a chord with me. To be fair, Hayao Miyazaki's Spirited Away (2001) almost made my top-ten, but the sheer virtuosity of Pixar’s computer animation on WALL-E (2008) just blows me away. And, guilty confession this, Happy Feet is another passion, just because the snow effects are so mind-boggling (not to mention the story, environmental message and terrific songs). However, WALL-E wins out on a personal level – just because I know what it feels like to be alone. Enormously funny, hugely inventive and mightily pertinent, the film chronicles the solitary life a solar-powered robot – WALL-E – who, seven hundred years after the apocalypse, is still sorting out the waste left behind by the human race. With only a cockroach for company, our hero goes about his business, periodically fixing himself up with odd parts, while collecting fragments of a previous human existence that takes his fancy, such as an old video of Hello, Dolly! He particularly likes the song ‘It Only Takes a Moment,’ because it conveys the possibility of companionship (“Your heart knows in a moment/You will never be alone again…”). Then, one day, WALL-E comes across a robot probe called EVE… It’s not until much later in the film, when our ecological protagonist encounters a new realm, that we are reminded we are actually watching a cartoon. The effects, lighting and focusing techniques are that realistic.

Only the lonely: Andrew Stanton's WALL-E

The fascinating thing about this exercise is discovering how films have shifted away from one’s memory of them. Even if, on a more recent viewing, Fanny and Alexander now seems more macabre than I recalled, it still exerts enormous heft and richness. In the future it will be interesting to look back on the films that have made as much of an effect on me now as those classics in my youth did then: relatively more recent films like My Life Without Me, Tulpan and I Origins. Just thinking about them makes me want to reach for my DVD remote.

JAMES CAMERON-WILSON