70 Years of Film Review: Mansel Stimpson

Mansel Stimpson’s

Top Ten Films of the Last Seventy Years

Rope (USA, 1948, Alfred Hitchcock)

The Happiest Days Of Your Life (UK, 1950, Frank Launder)

Last Holiday (UK, 1950, Henry Cass)

Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (USA, 1953, Howard Hawks)

Tokyo Story (Japan, 1953. Yasujiro Ozu)

Orders To Kill (UK, 1958, Anthony Asquith)

Peeping Tom (UK, 1959, Michael Powell)

The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (France/West Germany, 1964, Jacques Demy)

Nicht Versöhnt (West Germany, 1965, Jean-Marie Straub)

A Chorus Line (USA, 1985, Richard Attenborough)

A key feature in Film Review annual in recent years was the Introduction written by my then- co-editor Michael Darvell. Although he has each time picked up on recent events in the world of cinema, his Introductions have time and again also harkened back to past decades and to his own memories of cinema-going then. I have written nothing in that vein myself, but the idea of picking my favourite films of the last seventy years has resulted in this piece which is very much along those lines.

I made my selection in the simplest possible way by picking out the films that I have viewed most frequently (all but one have appeared as DVDs but all ten were first seen in the cinema). What strikes me on looking at the list is the fact that over half of the titles were films that I came across between 1950 and 1960. Although I had been taken as a very young child to a war-time re-issue of Walt Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, it was in the late forties that I fell in love with cinema so the emphasis on this period could be put down to nostalgia. However, my continuing pleasure in these films means that in this critic’s eyes they have stood the test of time. I am therefore prompted to ask if these years represented a golden age of cinema and not least in this country (many British filmgoers admit to preferring Hollywood movies to home product but four out of six of my titles from this time are from the UK).

In discovering cinema from 1949 onwards, I was doing so in the age of the great Ealing comedies and both Kind Hearts and Coronets (1949) and The Lavender Hill Mob (1951) were strong contenders for my top ten. But, ironically perhaps, it is two non-Ealing British comedies that came out on top. When the farce The Happiest Days of Your Life went on release in 1950 (oddly enough accompanied by Robert Flaherty’s Louisiana Story), I saw it twice within a week. Admirably succinct at 81 minutes and adroit at hiding its stage origin, the comedy is built around the idea of a ministerial error that results in the same premises being shared by two schools, one for boys and one for girls. But, if John Dighton’s concept was promising in itself, what made it glorious on screen was the casting of Alastair Sim and Margaret Rutherford as the two school heads, both on peak form. With supporting roles for Joyce Grenfell and Richard Wattis and lines that Terence Davies fondly quoted by heart when I interviewed him years later for the London magazine What’s On, who could wish for anything more? Not me.

Margaret Rutherford, Joyce Grenfell and Alastair Sim in The Happiest Days Of Your Life

Just one month later I discovered Last Holiday starring Alec Guinness and Kay Walsh, the ironic story of a man who, having been informed by his doctor that has has not long to live, goes to a posh hotel where he finds that in all other respects luck is suddenly on his side. One of the very first interviews that I did for What’s On was with the Finnish filmmaker Aki Kaurismäki who surprised me when speaking of his admiration for an Ealing comedy. Only afterwards did the penny drop: with its combination of humour and pathos foreshadowing his own work, it was Last Holiday to which he was referring but he had not realised that it was made by Associated British. A screen original by J. B. Priestley, it had some critics querying what it was all about. However, part of its appeal to me was that I found it crystal clear that Priestley’s tale was a topical comment on the way that the war had brought the British people together only to have the post-war era reasserting the more traditional society in which class mattered. In passing Last Holiday also offered another unexpected delight: a brief appearance by the only woman eccentric who could evoke thoughts of Margaret Rutherford without in any way being overshadowed by her. The cast list gives her name: Madam Kirkwood-Hackett!

A final romance: Alec Guinness with Kay Walsh in Last Holiday

It was also in this period that the Classic repertory cinema chain enabled me to catch up with other also runs such as Green for Danger (1946) and Brighton Rock (the Boulting Brothers version of 1947). On the other hand I was old enough to see The Third Man (1949) and All About Eve (1950) on their first release. It would only be in later years that I would come to admire such Powell and Pressburger masterpieces as A Matter of Life and Death, but the depth of human feeling drew me at once to the less showy films of Anthony Asquith. But if both The Winslow Boy (1948) and The Browning Version (1951) (with Michael Redgrave at his most moving) were strong contenders for my Top Ten, they had to yield to another of Asquith’s films which I find his most satisfying of all, the later Orders to Kill. The screenplay was by Paul Dehn whose work as a film critic I had much admired. He was telling the story of a former pilot sent on a wartime mission to France and consequently expected to kill face to face for the first time. Dehn described it as a film about the difference between war and murder – if any. The film justly won an award for Irene Worth’s unforgettable performance, was brilliant in its use of Benjamin Frankel’s music score and contains the best possible of last lines which captures perfectly the irony and pathos at the heart of this work.

Eddie Albert and Paul Massie in Anthony Asquith's Orders to Kill

As the fifties went on I found my critical interest in films leading to a fascination with the way in which a director’s treatment of the material could add to my pleasure. Two works stood out in this respect. First, in 1952 I caught up with what was to become my favourite film by Alfred Hitchcock, the 1948 production Rope famous for its ten-minute takes and the absence of any editing as such. Most people prefer other works of his, but I regard Hitchcock as a brilliant entertainer who delighted in playing games with his audience. And that was what he was doing in Rope. When introducing a screening of this film at the National Film Theatre in 1999 I made a deliberately controversial comment by declaring that Hitchcock was the very best of the second class of filmmakers (I was making the serious point that if cinema is an art form then the finest directors deal with the human condition and personally I feel that Hitchcock only once did that whole-heartedly – in 1957’s The Wrong Man). However, he has rarely if ever been matched as a director of thrillers and I am in awe of the ways in which in Rope he manages to make the substitution of camera movement for editing a source of even greater effectiveness.

Farley Granger, John Dall and James Stewart in Hitchcock's Rope

The other film that had me marvelling at the director’s touch was Michael Powell’s controversial Peeping Tom which initially received the same kind of critical disapproval for its bad taste as did Hitchcock’s magnificent Psycho (1960) a few months later. Powell’s glorious but not always reliable autobiography gives the impression that the abuse for Peeping Tom was such that it was quickly withdrawn from cinemas. Not so. I saw it first on its suburban London release in May 1960 and then again when it came to the ABC cinema in Eastbourne in October of that year. If I admired it for its direction (including the intensity achieved at the very start by showing us a view through a camera lens with the focal lines in place), it was also notable for doing what exploitation films never do: it made the serial killer played by Carl Boehm a victim of his upbringing and therefore worthy of pity.

Carl Boehm in Michael Powell's highly controversial Peeping Tom

The period on which I have been focusing was also the age of Marilyn Monroe who has to be represented here. It may not be her best role, but what these days has become the underrated Gentlemen Prefer Blondes is my choice. Containing no wasted frame, Howard Hawks’s comedy with music (great songs, witty lyrics) represents Hollywood at its best and Marilyn and Jane Russell make a great team. Out-and-out musicals can also be mentioned as a reason for this being a golden age. The film that converted me to musicals was Annie Get Your Gun (1950) with Betty Hutton, although I now regard Call Me Madam (1953) as an even finer example of a Broadway show made into a film.

Marilyn in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes

However, we go to a much later period for my favourite musical of all which has to be Richard Attenborough’s appallingly under-appreciated A Chorus Line. Best seen on the biggest screen available, it’s the only movie I know that can cause the same shiver of appreciation down your back as can be encountered during the best musical moments in the theatre. The cast is talented, the music distinguished, but what makes the film exceptional is the direction (Attenborough never did anything better in that capacity). Musical numbers on screen need to flow, the editing assisting instead of interrupting and with no dialogue inserted to distract (how I hate the 2001 Moulin Rouge!). The fact is that Attenborough can do that better than almost anybody else. You might not have expected it of him, but a feeling for music is probably inborn and I don’t think that it is an illusion that I have a childhood memory of Attenborough as a radio disc jockey introduced by the tune ‘Open the Door, Richard’. When the NFT late on in his life mounted a season in tribute which he attended, the lack of interest in A Chorus Line caused it to be transferred from NFT1 to the small NFT3 and when giving his introduction to it he can hardly have been unaware of what that meant. They kept the lights on long enough for him to walk back up, slowly because of his age, and I took the chance to speak as he did so. I said: “If you don’t mind a comment from the audience, I’d just like to say that this is not just a good film musical, it’s a great one”.

‘Dance: Ten; Looks: Three': Audrey Landers in A Chorus Line

Those who read my reviews will be aware of my keen interest in foreign language films so that the presence of only three of these in my Top Ten could come as a surprise. There is, for example, no Bergman (Winter Light from 1962 comes closest) and no Bresson (1959’s Pickpocket just ahead of 1956’s A Man Escaped) and, sadly, Godard’s Vivre Sa Vie (1962) with the wonderful Anna Karina did not quite make it. This probably reflects the fact that I seek a degree of relaxation in the films I watch the most. The French film that does get in is The Umbrellas of Cherbourg since I admire the individual world that Jacques Demy created on film. But two elements in it took it to the top even more than its colour design and use of music with lyrics replacing dialogue. First, there is the scene in which the lovers part at the station when the boy leaves for military service. It is full of the intense feeling of first love but also captures perfectly the sense of a time that will never come again and can never be recaptured. It is one of cinema’s great scenes. Secondly, I find – and this will be contrary to the interpretation of some viewers – that the ending illustrates our tendency to believe in some perfect alternative life but one that in fact might never have been: our heroine may have lost her first love but would life with him really have been better than what she has found as a wife and a mother with a good man? Quite possibly not.

Catherine Deneuve and Nino Castelnuovo in The Umbrellas of Cherbourg

The only film on my list not seen on DVD is the film that I have paid to see more often than any other: Jean-Marie Straub’s Nicht Versöhnt variously translated as Unreconciled or Not Reconciled. Usually I am not easily engaged by avant-garde cinema but this adaptation of Heinrich Böll’s novel Billiards at Half Past Nine is a haunting look at German history in the 20th century, an age in which an architect can build but war will destroy and in which unforgivable acts may be allowed to fade from mind. Authentically Germanic, admirably brief (less than an hour), it persuades you that it will reveal more on each viewing. It may not actually do so, but I keep returning to it as when I saw it twice in one evening at the NFT. In any case the image of a woman who doesn’t forget the past dressed to go out and collecting a gun kept in her greenhouse is indelible.

Nicht Versöhnt

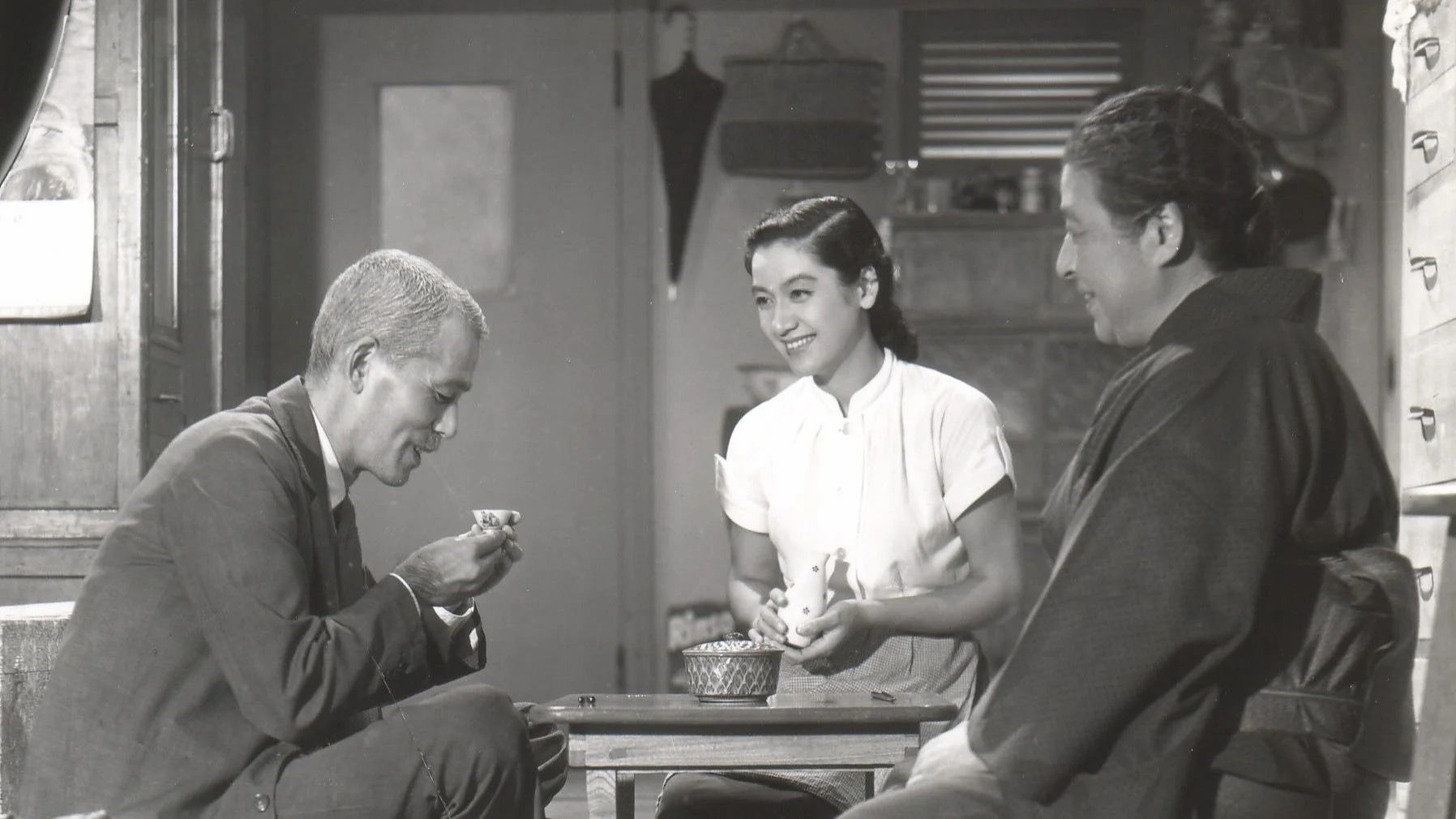

Finally, my favourite director, Yasujiro Ozu. The Japanese master’s most popular film Tokyo Story is amongst his very best. As so often in his work, the film centres on family life combining what is quintessentially Japanese and what is universal. The people may be played by actors including Ozu regular Chishu Ryu, but they come to seem like actual people one has known. Like many a truly rich work of art, it can sustain more than one interpretation as it tells of elderly parents on a visit to Tokyo to see their children and grandchildren and also the widow of a son who had died in the war (Setsuko Hara). The latter takes time off from work one day to show the visitors around; it’s a small gesture but because of it what is in other ways a disappointing trip supplies a happy memory for the mother who, as it turns out, will die on her return home. Thus a life ends happily rather than unhappily to the extent that this action by her daughter-in-law has come to colour her feelings in what prove to be the last days of her life. The most quoted lines in Tokyo Story are the dialogue exchange about life being disappointing, but for me that’s not what Ozu is telling us. There is disappointment, yes, but there‘s happiness too. In an Ozu film every detail counts and at the close a ship passes but, as it does so, its hooter is heard. Life goes on. Tokyo Story is a film for all time.

MANSEL STIMPSON

Yasujiro Ozu's Tokyo Story